Selective Mutism is an anxiety-based condition in which children are unable to speak in specific situations. The child or young person may be chatty and confident at home, or in comfortable situations (sometimes described as ‘talking nineteen to the dozen’!) but communication may reduce dramatically, or even become non-existent in situations they perceive as more demanding or unsafe. The swing between the two states can be striking; the reduction in communication can even include gestures and facial expressions, which can sometimes lead to the child being perceived as ‘distant’, ‘aloof’, ‘stubborn’ or ‘just shy’. Sometimes, the circle of ‘safe’ people for the child to speak to can be as narrow as one person in the immediate family, feeling too anxious to speak to even wider family such as grandparents. If a child doesn’t speak at home or at school, or stops speaking suddenly, this is unlikely to be selective mutism, and should be referred to SALT. There is no current pathway (at the time of writing) for children with Selective Mutism within SALT. This is due to the anxiety-based nature of the condition, so it is felt support to manage anxiety will be more beneficial than Speech and Language specific intervention.

Some children with Selective Mutism are able to communicate with some people outside their ‘safe zone’ when they deem it necessary, such as answering a direct question from a teacher. This does not mean that they are not selectively mute, but that their compliance and fear of breaking rules have made the thought of not responding more frightening than their fear of speaking aloud. The responses will tend to be minimal, and only when completely necessary. Children with selective mutism are generally predictable and consistent in their responses to differing situations. These children can be described as experiencing ‘low profile’ selective mutism, as opposed to those with ‘high profile’ selective mutism, who are unable to respond at all to those outside their safe circle.

Because Selective Mutism is an anxiety-based condition, children are unlikely to ‘just grow out of it’. It can be thought of as a phobia, so children are likely to develop their own coping strategies which can sometimes be less helpful (e.g., complete avoidance of situations perceived as stressful, sometimes leading to Emotionally Based School Avoidance (EBSA)). Most schools are likely to have at least one selectively mute child on roll, so developing a plan of support is likely to be useful!

As always, best practice is to follow the APDR cycle:

Assess: Where is the child comfortable speaking? Who are they comfortable speaking to? What are the maintaining factors currently in place? (e.g., pressure to speak, disapproval/punishment, removing the need to speak, parental anxiety, assignation of silent ‘role’, no need to change, expectation to change without appropriate understanding and intervention)

Plan: how can the maintaining factors be removed, and the comfort factors increased? Set appropriate levels of challenge to widen the child’s ‘safe’ circle, e.g., silent participation alongside others; playing nonverbal games: Guess Who, snap; tolerating voice being heard by bystander, either in person or via technology.

Do: Talk to the child about their selective mutism and anxiety, and share the plan to help. Consistently implement planned strategies and support, for at least 10 sessions.

Review: Set a time to review impact and identify ways forward. What has been working, what hasn’t worked so well?

Autistic children are more likely to develop selective mutism than neurotypical children, perhaps as a result of the higher levels of anxiety and sensory processing differences they may experience. If a selectively mute child in your school also has communication challenges, consider adding them to your next Consultation and Review Meeting (CARM) to discuss with your Autism and Social Communication Team advisory teacher. We can help you plan interventions, review progress and suggest additional support strategies to try.

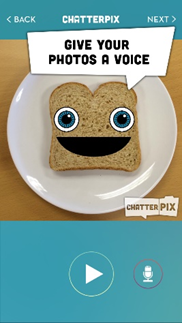

Children may enjoy games such as Guess Who, or Top Trumps, which can be played nonverbally, or with minimal verbal interaction. Walkie-talkies can be a surprising hit for increasing the distance over which they are willing to speak and sometimes the number of recipients they are happy to speak to. Apps and toys which record the child’s voice, such as Chatterpix (available for both android and Apple devices) or Talking Tins can also be used to help the child to get used to hearing their voice in more public situations. Books such as The Loudest Roar, by Clair Maskell, or Halibut Jackson by David Lucas can be a useful starting point for discussion with children. Older readers may prefer the Alvin Ho series, by Lenore Look and LeUyen Pham, or A Quiet Kind of Thunder, a young adult book written by Sara Barnard.

One recommended resource is The Selective Mutism Resource Manual, which includes a number of practical suggestions and therapeutic activities, as well as resources to share with families and other professionals.

Further information for schools and parent can be found here, at SMIRA, the Selective Mutism Information and Research Association.

Tools for Schools

Tools for Schools